A Triad Of Nightmares Shadows Farmers Surviving The Boko Haram Crisis

A glance into how the Boko Haram conflict, resource scarcity, and climate change affect farmers’ livelihoods in Nigeria's northeastern Borno State.

Sometimes the cost of working on a farm in Borno could be as simple as struggling to source agricultural resources to grow crops. Other times, it could be facing the risk of death. For 43-year-old Abubakar Haruna, it meant narrowly escaping the clutches of Boko Haram after the insurgent group descended on Dala Malari in the Jere Local Government Area.

He briefly stops spraying the content of the knapsack sprayer strapped to his back as he narrates his ordeal of surviving the insurgency while cultivating beans, carrots, groundnuts, onions, pepper, watermelons, and sometimes maize.

Abubakar has rented the piece of land for almost four years after fleeing Kirenowa, a town near the shores of Lake Chad that houses one of the pumping stations for the giant irrigation project in the region. Despite leaving his hometown, the war has shadowed him as it does for many others.

He has watched Boko Haram insurgents rustle animals such as cattle and sheep. Another time, it was a cat-and-mouse chase after the group swarmed the location. “I was watering my onions when I saw Fulani [herders] running. I asked what happened. They said can’t you see?” At that moment, he noticed the insurgents in pursuit of the herders.

“I ran and switched off my [water pump] generator,” he recalls. When one of the insurgents saw him, he also took to his heels.

Not every farmer is lucky enough to come out of an encounter with the insurgents unscratched. In May, insurgents with the Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP) killed at least 45 farmers and local guards in Rann, the headquarters of Kala Balge Local Government Area.

One of the most horrific massacres in the state that also rattled the country was when, in Nov. 2020, Boko Haram killed at least 110 people working on rice fields in the Koshebe area of Jere. The Nigeria International NGO Forum (NIF) would later reveal that more than a hundred farmers were killed across Borno since the beginning of the farming season in June of the same year.

Insecurity is, however, just one of the farmers’ concerns.

The farmers struggle between a rock and a hard place, especially those suffering from the impacts of displacement, climate variability, and insecurity amid difficulty accessing agricultural resources and livelihood opportunities. In July, a food crisis assessment brief estimated that 4.1 million people would face hunger and severe food insecurity this lean season in the Northeast.

Farmers also face challenges with seasonal water scarcity and extreme erosion. Meanwhile, one farm in the area has adopted safeguards against these trends and potential effects of climate change.

Climate change

Before arriving at the farm, we had to navigate through a giant crater swallowing nearby farmlands. The cavity was formed as a result of unsustainable excavation by sand miners working to earn an income and feed the construction industry. The effects of unsustainable practices are visibly devastating to the local environment, and the situation is worsening due to the sandy nature of the soil and the lack of trees to slow down or prevent the continuous collapse of the walls around the crater.

The erosion in the areas is also visible around the path of the seasonal Ngadda river, where a farm adjacent to the water body has adopted nature-based safeguards. The manager, Ahmad Bukar, tells me that a sand barrier was constructed to shield it.

An afforestation initiative, which seems to be the best escape from the unforgiving bright sunlight, is helping to restore and conserve the land neighbouring Abubakar’s farm. Unlike most of the exposed farmlands in the area without vegetation, this farm is surrounded by several trees and has an orchard consisting of shrubs planted in rows.

Ahmad says the farm planted 1,500 seedlings of lemon and other trees like mango to reclaim about three hectares of land. The farm also has Jatropha, which protects the soil and helps with fertility. It achieves this through nitrogen fixation: absorbing gas from the air and injecting it into the ground. This process is an incentive for farmers in the region due to restrictions on the use of NPK fertiliser because of its use in the production of improvised explosive devices.

The high dependence of the local population on agricultural resources means juggling between insecurity and climate variability risks. Ahmad, who doubles as the Director of Operations at the African Climate Change Research Center’s Northeast field office, says in this part of Borno, “the challenge of the farmer is the constant change of water cycle, which costs them a lot.”

He then cites an example. When there are two or three bouts of heavy rainfall, farmers rush to the farm, clear the ground, and plant seeds. But, afterwards, the rains disappear. “So there is a kind of confusion on how to plan or when to plant a seed. You know one thing with seeds when they are not rightly planted at when due, then definitely there will be a problem at the harvest period.”

The farm invested in boreholes to complement water sourced from the Ngadda river. The river also serves as a reservoir, but it dwindles during the dry season. When we visited in June, the river had vanished, and a tractor was preparing a section of the floodplains for rice farming. HumAngle would later learn that the investment was washed away due to a high volume of water this year, which has caused devastation along the path of the river.

The farmers here have to cope with a lot of trends outside their control, including by walking long distances due to the trenches surrounding Maiduguri. The distance also makes it difficult to evacuate harvests.

“You know, a farmer can produce 10 to 15 bags and you can’t expect him to carry it on his head. He requires a means of transport that isn’t there,” Ahmad explains. Another problem he mentions is the urgent need to evacuate at the end of the harvest before the insurgents move in to steal.

The general restriction on movement means farmers have between 9 a.m. and 12 p.m. to work. People who stay longer risk being chased by the military or, worse, Boko Haram insurgents. But the security situation in the area has recently improved.

The fight for survival

The insurgents on the route to the farm flog people after searching and not finding a phone and money, laments Ahmadu Aga, a displaced farmer from Boboshe, a community in central Borno.

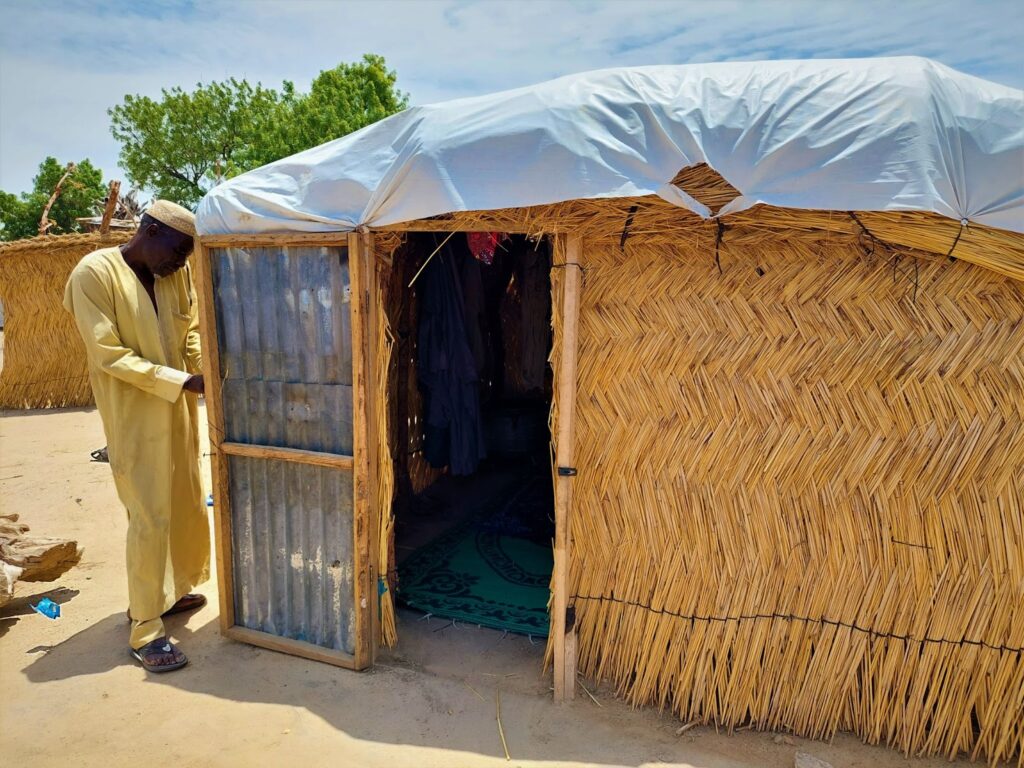

I met him in a makeshift thatch house at Muna Garage El Badawe camp situated on the outskirts of Maiduguri. The door had reinforced Zinc, while the roof had white tarpaulin spread to control rainwater and sunlight. Even though the materials represent the structure’s temporary nature, they allow internally displaced persons to navigate the hot climate and resource scarcity.

In Boboshe, Ahmadu used to grow onions, sorghum and firgi, a dry-season variety called dwarf sorghum. The father of 18 and husband to two surviving wives describes his previous life with nostalgia.

“There was life,” he says.

Living conditions had become tough after Boko Haram established a presence. He only got to flee in Feb. 2016 during a military operation. However, not everyone made it. Eighteen people were killed after the soldiers that stormed the town opened fire. At night the survivors gathered and buried the dead and discussed the next line of action, fleeing to another town.

When the group finally arrived in Mafa, he says the soldiers at the gate held them there while insinuating that they were Boko Haram members because the insurgents stayed in the town without resistance.

They would later receive water and instructions to stick to the road as they headed to Maiduguri. On arrival, the authorities held them at the gates for days. Eventually, they transferred them to the camp after screening by Intelligence agents and giving them food aid of bread, sardine, and water from the Red Cross. The aid organisation would subsequently provide more relief supplies in the form of tarpaulin and food. Eighteen months later, it replaced the food aid with cash disbursements of ₦35,000 ($83), which lasted for eight months. “It’s been almost four years since the Red Cross left,” Ahmadu says.

Hunger became an issue after the government’s emergency management agency took over. According to him, it’s been three months since they brought food. The IDPs’ records showed there were only about 36 or 37 deliveries in four years although the agency was supposed to provide monthly supplies.

The uncertainty surrounding food deliveries makes farming an essential livelihood for displaced people. However, this is complicated and risky due to the scarcity of agricultural resources and the activities of insurgents.

Trips to the farm closer to Ahmadu’s camp are safer, unlike the one located farther away which is associated with persistent safety risks. The farmers leave at 1 p.m. after working for a few hours because once it’s 2 p.m., there are often insurgents around.

“You are not dead, you are not alive,” is how Hagola Biya describes his farming experience.

This contrasts sharply with his former life in the Siga Baja area of Boboshe, which was one of abundance. Things were cheap, says the father of 14 and husband to two wives. He recalls working with labourers and harvesting about a hundred bags of onion annually (the sacks were much smaller than those used now). Millet fetches 30 bags, and 10 bags of beans are collected from the same farm, while a separate beans farm brings 40 to 50 bags in addition to 40 bags of dwarf sorghum.

He initially fled in 2014 to a village about 10 km away. The insurgents frightened them, he says. Apart from gathering the people and urging them to follow their doctrines, they began setting up a roadblock to search those returning from the market. You got flogged if tobacco is found.

After settling down in Maiduguri, the Red Cross issued him a feeding card, but that aid stopped about three years ago. According to him, he began farming in a college field after arriving in 2016, but he later lost access to the land. He switched to an irrigated farm about 5 km away and a seasonal sorghum farm farther away in Ngom, respectively costing ₦70,000 ($165) and ₦15,000 ($35) to rent. One of the challenges here was the fertility of the sandy soil, which was different and poor compared to the type in his hometown. He says the situation is tougher with onion farming due to a lack of access to urea fertiliser.

Last year, he got 75 bags of onion. But the sorghum farm suffered from the reduction in rainfall. We got 10 bags of sorghum, although I was expecting 30 based on cultivated land. He complains that the beans were also affected by a shortage of water which occurred after they had started growing. The output further declined after an unexplained fire outbreak. He had gotten five bags instead of the expected 20.

The effects of climate change, particularly unpredictable weather conditions and rainfall variability, distort the planting and harvesting seasons, in addition to increasing food insecurity and hunger in farming communities.

This year, Hagola expects better rainfall conditions. “We planted sorghum almost two to three times last year due to the water shortage, but this year after planting once it has sprung up, water came early,” he explains.

Earlier in the year, Nigeria’s Meteorological Agency (NiMeT) predicted the onset of the planting season would be normal in most parts of Nigeria, with a few areas having it earlier while some will have it delayed.

The challenge of the farmer is the constant change in water cycle. There is a kind of confusion on how to plan or when to plant.

– Ahmad Bukar

However, erratic rainfall is not the only challenge. The threats from insurgents also cast a shadow on farming activities. “I have not seen them; they come when you leave,” says Hagola, who leaves his farm between 1 and 2 p.m.

The risk has now taken a new dimension with a new trend involving the abduction of farmers, who are only released after the payment of ransom. The military organised a dialogue to persuade them to comply with the security restrictions, but the soldiers were unaware of the distance to the farms.

“They told the farmers they could set off after the road was open at 6 a.m. and return at 10 a.m. They think the farm is close by, but the farmers have to go farther due to lack of access to land,” Hagola says. “The Bulamas protested that 10 a.m. was not feasible because some farms were far, and the soldiers requested what time would be suitable, and the group echoed 1 and 2 p.m.”

The military would later review the restrictions to 2 p.m. It also advised the farmers not to go far and move in groups.

Recently, six farmers were reported to have gone missing after they went to their farm at Bulagarji, a village a few kilometres from Mafa town. The attack occurred the same day officials screened and cleared farmers go out to their farmlands.

Hagola also faces relocation as part of the government’s efforts to resettle displaced persons back to their communities, but the programme is marred by safety and livelihood concerns. He says Boboshe is still not safe, in response to questions on what would happen after the closure of the camp. “We follow our Hakimi, whatever he says. If he says we should go to Dikwa, even if we leave during the rainy season, the plan is to move the family.”

In any case, he would hang around until the end of the farming season. He also has an agreement with the farm owners here that allows him to return if he goes and is unable to find where to farm.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter