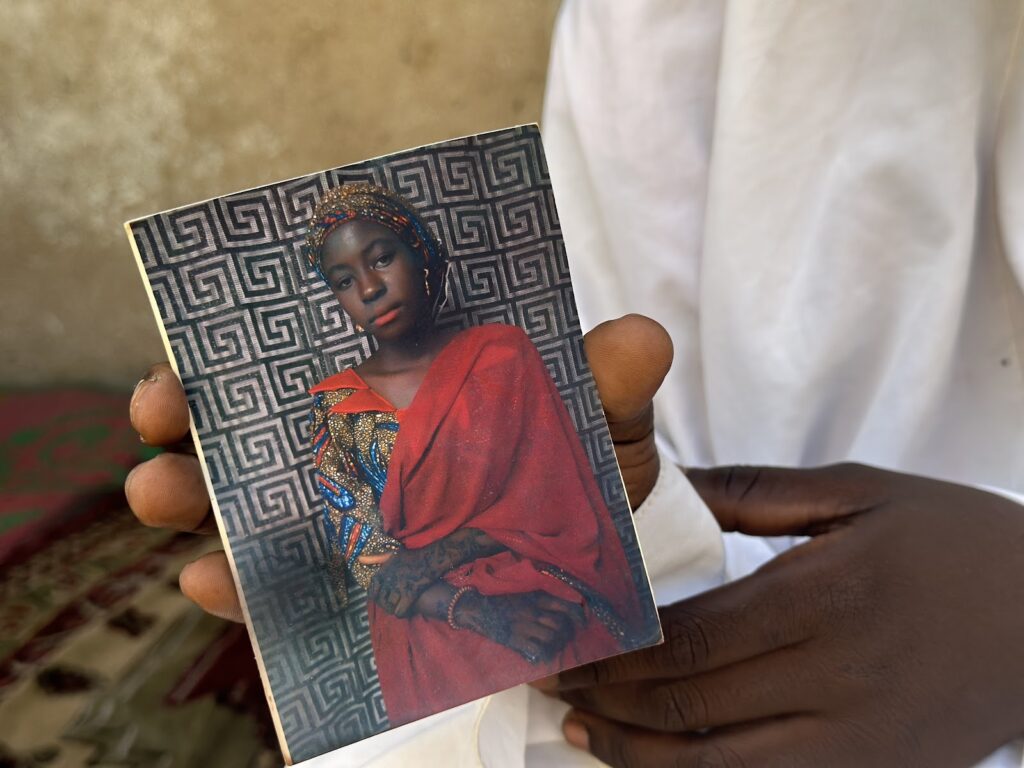

Yakaka Alhaji Aisami did not know it when she woke up that morning in April this year, but two things were going to happen to alter the trajectory of her life. She would receive a delicious bowl of pap from her doting niece, setting off an unexpected chain of events that would culminate three days later in the cold-blooded murder of her 17-year-old firstborn child.

In her home in Bama, Borno State, northeastern Nigeria, she speaks to me with so much anger about the events of that day so rapidly that sometimes, her words run into each other, and she has to pause for breath. Her hands gesticulate energetically, and her eyes have so much darkness it is the first thing I notice about her.

It was during this year’s Muslim Ramadan fasting period, which ran from March to April, a time they all observed. After breaking her fast in the evening, she took a sip of the pap and reeled at how delicious it was. She was heavily pregnant at the time and enjoyed local cuisines a little more than usual. Her daughter, Falmata, must simply experience that deliciousness with her, she told the girl, pouring some into a cup and offering it to her. They had a relationship that was based on true friendship, and they related to each other well. Falmata had just finished cooking in the open compound with firewood. It was terribly hot that evening.

When Falmata finished transferring the food from the pot into a flask, she came over to taste the pap and declared it was not as delicious as her mother had made it out to be. Her mother reminded her that she (Falmata) had just had watermelon, which she had also sweetened with some sugar first. She said it was bound to have mildly altered her tastebuds, explaining why she may not have enjoyed the pap. Falmata agreed with this explanation but remained unable to down the rest of the pap that had already been poured into a cup for her.

“Okay, Auntie,” she told her mother, agreeing to drink it again later. It is common among close-knit modern-day Kanuri families for daughters to refer to their mothers as auntie. It is a form of endearment in that context.

They shared the compound with her husband’s younger brother, whom they called Awana (the Kanuri term for paternal uncle). Her husband, Ba Bunu, was away in Chad for business and only returned once a year. The family had been displaced years before by the Boko Haram insurgency and had fled to Chad at the time. When they returned to Bama in Nigeria, they decided that Ba Bunu should stay back since he had started a trade there.

Having heard the whole conversation about the pap, Awana emerged from his side of the compound when he was done eating, yelling at Falmata and accusing her of disrespecting her mother.

“He came out of his room ranting,” Yakaka still remembers his exact words. “He said, Stupid child. Is she not your mother? Why would you talk to her like that? Why would you be talking back to her? Wallahi, I will deal with you right now, you disrespectful brat.”

Both mother and daughter were puzzled by this outburst as they knew nothing was disrespectful about the exchange they had just had. Falmata, who had remained quiet for most of his outburst, finally expressed this to her uncle. He had a history of hitting her and had left her with scars in the past, she reminded him. She told him she would not sit back and allow him to do it again this time.

Her response angered him even more. He thought it was unthinkable that Falmata would talk back at him like that. “He said, How dare you talk back at me? I will kill you today.”

In societies that place that much respect between a child and her older family members, and one where misogyny seems to be a huge problem, Awana thought her talking back at him and standing up for herself was unforgivable and brought dishonour to the family. He would kill her, he vowed. The result of this thought process, which turned out to be the carefully planned, brutal killing of Falmata, reflects the vulnerability of women and girls all over the world for flimsy reasons and how misogyny is a direct cause of honour killings. His family’s subsequent refusal to condemn his action was also a tragic symptom.

Falmata dared him to touch her and see what would happen. They continued to exchange heated words while Yakaka tried to calm them down. The man was unrelenting, and Falmata had had enough of his maltreatment of her over the years and would no longer be quiet about it. Suddenly, Awana went to the fireplace that still had the burning firewood from when Falmata had just finished cooking and attempted to attack her with it. Falmata also grabbed a wood in defiance. Yakaka tried to hold them apart but made very little progress. She had no clothes on, only a wrapper tied around her chest. She grabbed a hijab from her room and returned, attempting to separate them.

“Usually whenever he starts making trouble, he is hard to restrain. He would only stop after doing whatever he intended. He listens to no one except the girl’s [Falmata’s] father. He is the only one he fears. I have a health challenge; I have high blood pressure. I was also pregnant at the time. So, my heart was rapidly beating at that moment. And my head was spinning. They were both shouting at each other. I finally got to drag out my daughter and take her to my brother’s house. I told my brother: Awana has started again,” Yakaka recalls.

Afterwards, she contacted her husband using the voice note feature on WhatsApp and explained what had just happened.

“He told me exactly what I had just told you about Awana. He said Awana is stubborn. He listens to no one.”

He then enquired about Falmata, and Yakaka told him she was in her brother’s house. She, Yakaka, had left the house, too. She had had enough of his behaviours. Her husband said he would return home to settle the matter, but Yakaka said she did not see a need yet, so he stayed back. For three days, she and her husband dragged the matter over the phone as he begged them to return home.

Meanwhile, Awana kept telling anyone who cared to listen that he would kill Falmata. He had dug her grave, he said, and if he could not kill her, then he would kill her mother. As he made the threats, he sharpened a cutlass publicly.

By this time, Falmata’s father recognised the gravity of the situation. He also knew it would take him time to make the trip back to Nigeria by road, as flying was not an option he could afford. So, he contacted his older brother, who lived in Maiduguri, a mere hour’s drive from Bama, and asked him to make the trip to Bama to resolve the matter.

“I was even on the phone with my husband as he enquired if his brother had arrived when the man walked in,” says Yakaka. It was about 10:30 p.m., but most people were awake as it was during Ramadan. Around 2 a.m. that day, the rift erupted again between Awana and Falmata. While Falmata was taken to her mother’s family house for her safety, she refused to stay there.

“Her heavily pregnant mother’s health was deteriorating as a result of all the chaos, so all she could think about was her mother. She also refused to stay in the same house as Awana,” Yakaka’s older sister recounted.

As things continued to intensify, Yakaka’s older sister updated Ba Bunu over the phone. She said she intended to involve the authorities as things were worsening and his brother’s intervention was not helping. Ba Bunu agreed. The matter was then reported to a community head. While the main community head was not around, the Aja – a representative of the Bama emirate council – was around. He mediated between them. In the end, Falmata was made to apologise. “Awana is my father’s brother. I consider him as a father. So, from today henceforth, the way I will not talk back to my father, I will also not talk back to him. Please forgive me [to Awana],” Yakaka remembers her daughter saying.

Everyone was happy to see that the matter had been resolved.

This happened at around 10:15 p.m., and Yakaka had to spend most of the day at the hospital and was even on an IV drip to stabilise her health. When they returned home, she refused to eat while insisting on fasting the following morning, and Falmata became deeply concerned.

“Falmata said to me, Auntie, you were sick and hospitalised. You even had to spend the entire day on a drip. Why would you refuse to eat? Why would you refuse sahur [pre-dawn meal]? And how could you fast in such a condition? Let me cook you a meal. I said, ‘No, Falmata. It is already night. And I have no appetite.’ She refused to listen. And while she went out to set fire to cook, I lay down to sleep.”

At half past midnight, Yakaka recalls her daughter waking her up to offer her a bowl of pap that she had just made. After she drank it, she offered her her prescribed medications to take. She then poured more pap into the flask so that her mother would drink it if she woke up later and decided to take sahur, the predawn meal usually eaten by Muslims in preparation for the day’s fast. It would be her last act of kindness to her mother, but she could not have known this then. She had a strong sense of responsibility for her mother, perhaps because she was the first of five children and had to take care of things in her father’s absence despite her young age. She was in charge of cooking and even washing her mother’s clothes. Whenever she did anything to offend her mother, she would beg and cry and go into a depressive state until she forgave her.

“She never wanted anything that would upset me. She wanted my happiness and my happiness only. Everyone loved her. When I had the twins, she completely took over the operations of the house,” Yakaka reminisces, explaining how kindly Falmata treated her that night despite what an exhausting day they had and how it was all consistent with her personality.

After feeding her mother, Falmata felt sure she had done all that was expected of her. Exhausted, she lay down to sleep, pleading with her mother not to bother waking her up for sahur. She would fast without the meal, she said.

“She does not usually eat sahur. Usually, when I woke her, she would pray, drink some water and go back to sleep. This time, she decided not to wake up and even drink the water,” says Yakaka.

Far into the night, as both mother and daughter slept, Yakaka woke up to the dying, haunting screams of her daughter.

As she sprang awake and struggled to see in the dark, she saw Awana standing over her daughter, holding a sharpened piece of log that looked like an axe, dripping with blood she at first refused to believe was her daughter’s. She did not immediately take in the weapon and how brutal it looked, but the image would come to mind in the days that followed as she mourned Falmata.

“I vowed to kill her. And I did. Now you can do whatever it is that you want to do. I have dug her grave. You can bury her by 9 a.m. tomorrow,” Yakaka remembers Awana saying to her before exiting the place.

When Yakaka rushed to her daughter, she was barely conscious. She shook the girl repeatedly, calling out her name over and over, but she did not budge. Weeping and in complete shock, Yakaka held her daughter’s bloodied face. How could the daughter who just hours before was slaving away at the fireplace, so full of life and love in equal measures, now be staring at her devoid of both?

“When I moved closer and held her face, blood flowed freely out of her nose like a tap. As if you rapidly poured water out of a kettle. I exclaimed and took out my phone, and flashed her face with the light. She drew in air three times, and then she breathed her last. The pillow and carpet she was laying on that night were all soaked with blood.”

In a picture of Falmata’s corpse obtained by HumAngle, the last trickles of blood that poured out her nose had dried off, but the large pool of it that lay under her skull was still fresh. Her face had streaks of blood that had also dried. They ran across her forehead in slanted lines. Her lips hung slightly open, making a small part of her molars visible, and her eyes had been closed. She was wrapped around with a blue fabric tainted with pink and yellow, her hair undone. But for the amount of blood, one could be forgiven for thinking she was merely asleep.

Awana, having completed his mission, went back to his room calmly. He performed ablution and said his prayers, then lay down to sleep as though he had not just taken a human life.

Yakaka let out a series of screams that awakened the entire neighbourhood. She ran, like a mad person, she said, to her in-laws’ house and informed her brother-in-law. It was shortly before 2 a.m. that night. On reaching the house, she told him, “Come. Awana has done what he vowed to do. He has killed Falmata.”

Incredulous, he followed her to the house. “She is dead,” she wailed as they stood over her daughter’s corpse. The man disagreed, saying she was merely unconscious. “I told him I could tell when a body is lifeless.”

She got a couple more people from her family house, and they took Falmata’s body. She had started to go cold and stiff. They boarded a tricycle, locally known as Keke Napep, and headed to the hospital. First, they stopped by a police station and made a report. At the hospital, the doctor examined Falmata and declared her dead.

Just like that, her daughter was dead.

Though he would personally not categorise this case as a strict honour killing case, the conviction with which Awana killed Falmata and how righteously he believed himself to be acting are consistent with traits exhibited by people involved in honour killing, observed Dr David Markus Shekwolo, a forensic psychologist HumAngle consulted with the circumstances of this case. Dr Shekwolo currently works as a lecturer in the Psychology department of the Nigeria Defence Academy in Kaduna, with interests in terrorism, deradicalisation, and trauma counselling.

Honour killing involves the murder of a person, usually a woman or girl, by their family member (s) or on the instruction of their family member(s), often a man. They’re often motivated by cultural and hierarchical social values, with the belief that the victim has brought shame upon the family by going against set cultural norms. In this case, standing up to an elder.

From Awana’s unfounded accusation of Falmata speaking disrespectfully to her mother to him being enraged to the point of murder after she stood up to him, his belief that only death was enough retribution for “disrespect” was strong. While many honour killings are driven by factors such as perceived impropriety in sexual relationships, the victim’s decision to switch religion, etc., others stem from the violation of social or familial hierarchies, often carried out by lone family members. According to the United Nations, up to 5,000 women worldwide are victims of honour killings each year.

“In the man’s personal perspective, it is honour killing. That is how they look at it. Something that brings shame to the family, they believe to eradicate it is to delete the person entirely,” said Dr Shekwolo. Still, the crime remains a heavily subjective concept, especially when it is a lone family member acting on their own, like in this case and not the entire family. However, none of Awana’s family has openly condemned his actions. Some believe they were in support of it.

“Nobody has the right to take a life. We need to emphasise this,” Dr Shekwolo added.

“Honour killing is barbaric.”

He noted that if this case is left to go without punishment, it could contribute to a new trend of familial killings. While honour killing is not rampant in Nigeria or even West Africa, cases like Falmata’s, which bear a strong resemblance to it, suggest that it may be ongoing in rural areas, especially those dangerous to travel to. Bama is a village that has not been spared from the devastation of the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria’s North East. In 2014, it fell to the terror group as they fought to establish an ‘Islamic state’. Though the Nigerian army captured it back later, the village still has telltales of its brief stay in the hands of insurgents: some buildings remain burnt, and the village is largely undeveloped. The area is susceptible to occasional attacks, keeping it away from the reach of mainstream media. The trips to the village for this investigation were fraught with several risks.

There are many other towns and villages like this, and there is no telling the amount of gender-based violence that goes on undocumented, noted Dr Shekwolo.

Yakaka still cannot wrap her head around the tragedy. Even now, she speaks of the girl as though she were alive, as though the reality of her death was too complex for her mind to contain.

“They returned her corpse home. And people started to gather. The community head came. The district head also came after he was informed. He then took a picture of the corpse with his phone and sent it to the palace. The palace then sent someone who came and also took a picture of the corpse before she was dressed and prayed upon at 8 a.m. the following morning.”

Things went very rapidly after that. Her husband returned, but not in time for the funeral as it was quite a journey, and Islamic rules demanded that a person be buried immediately unless they passed at night. Yakaka tells me that everyone feared what he would do and how he would react. But when he arrived, he only crumbled under the weight of his helpless grief.

He wept profusely, and the pain turned him into a shadow of himself. He went into seclusion for many days, spending all his time praying for Falmata and for strength to carry on. He hardly spoke to anyone; when he did, it was to preach. He was home for a few months and returned to Chad just forty days after Yakaka gave birth.

After the funeral that morning, as Yakaka sat mourning and processing the brutality of her daughter’s murder, the suddenness of it, the Police arrested her.

“I didn’t sit to mourn her on the day of the funeral. I was there the whole day,” Yakaka tells me. “They said to me Awana made those threats continuously for three days. He continuously sharpened a cutlass in your presence. He vowed to kill you for three days. But you neither reported nor left the house for your safety. Therefore, you are being queried. We are arresting you.”

Her efforts in taking the girl away from the house for days until an authority mediated seemed to be of no consequence to them.

She spent the entire day at the station before being bailed out. The following morning, the police contacted her again to say the matter was being transferred to the Borno State capital, Maiduguri, where the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) is, and requested that she go with them. Very early in the morning, they travelled down to Maiduguri. They put both her and Awana in the same vehicle, and it was then she got a fuller view of the weapon he had used to kill her daughter.

“It was a big axe-like handle,” she said, demonstrating with her hand to equate its size to the entire length of her arm.

The police went with the bloodied carpet, pillow, and the weapon. When they arrived, the DPO asked Yakaka what she wanted. She found the question puzzling and asked him to do whatever was right.

When HumAngle contacted the Bama Divisional Police Officer (DPO), he explained that he was not allowed to comment to the media about cases, adding that only the headquarters could do so as the case had been transferred to the CID. When we reached out to the spokesperson of the Borno State command, ASP Daso Nahum Kenneth, he claimed not to have heard of the case before then and pleaded for time and more details to enable him to comment. We shared with him the full names of the suspect and the victim. Over several days, he promised to reply with comments but did not. Eventually, he stopped responding to phone calls.

“He [Awana] has given me a scar that I will never forget in this life. There is nothing that can take that away,” Yakaka says, with rage building again in her voice.

Awana has a history of violence against women. He used to hit Falmata every chance he got, leaving her with scars, which led to her standing up to him that day.

“You would be shocked by the size of logs he uses to hit her,” Yakaka says.

He also has a history of threatening to kill his wife whenever they fought. Yakaka remembers one particular incident that was so chaotic that he took a knife and attempted to stab her with it.

“I was the one who intervened and took the knife from him.”

Once, before this incident, she confronted him about how quickly he threatened to kill, urging him to focus instead on good deeds so that he could live a long and blissful life. He responded to her by saying that he already had a daughter who could inherit him and pray for him if he died.

“I asked him, What would she inherit? Your threats?”

Femicide is a growing concern in many countries in the world. In Nigeria, the DOHS Cares Foundation, an organisation fighting against SGBV and working to keep a femicide observatory, reported that between Sept. 21 and Oct. 22, 2024, it had recorded 12 femicide cases. In the past few years, there has been sustained outrage over the killing of women like Uwavera Omoduwa, a 22-year-old raped and murdered in a church she had gone to at night to study. In another case, 21-year-old Augusta Osedion was murdered last year by her boyfriend, Benjamin Best. Best had himself confessed to the crime in a series of posts made on social media. In both cases, the perpetrators have not been held to account.

Awana merely spent about two months in detention before he was released.

Yakaka was not exaggerating when she said everyone loved Falmata.

By multiple accounts, she was full of respect for her mother and everyone she knew. HumAngle spoke to neighbours in the area, and they provided many testimonies of her exemplary conduct.

“She was always calling those older than her as Yaya, Mama, or Baba. She would never call you by your name if you were older than her. When they first moved to this community, she started to call me ‘Yani Kura’. It became my name to every child,” one neighbour said.

Yani Kura is a term used among the Kanuri to address someone older than one’s mother. Yani translates to mother, and Kura translates to older. It is a respectful way of addressing the person to avoid calling them by their name, which is generally seen as disrespectful in some cultures in Nigeria.

Falmata used to weave caps and sell them for amounts that ranged from ₦13,000 to ₦14,000. She made one cap that was particularly exquisite and sold it for ₦25,000. She had not even been paid when she was murdered. The customer paid after she died.

The trauma of the entire experience was so severe that Yakaka struggled to function in the house. And when Awana was released by the police barely two months later, she could not bear it. She packed her things and her four children and fled the house. She moved to a different part of town and has maintained a low profile since.

“Because I am an orphan. It is someone whose parents are alive who can brag about having a support system. His parents are alive,” she says.

HumAngle found that Awana was now living with family in Maiduguri, the capital city. He went to his wife’s parents’ home to fetch her after being released. They refused to let him go with her because of the gravity of what he had done. He’s been living with a relative ever since. HumAngle has shared his exact location and contact information with the police.

After he was released from prison, he called Yakaka on the phone. When she answered and heard his voice, she could not believe it. She asked if it was truly her he had meant to dial or if it was a mistake. He said it was not a mistake and he was calling to check on her. That night, she could not sleep.

“I have nothing to tell him,” she tells me. “Not in this world.”

Yakaka Alhaji Aisami experienced an unimaginable tragedy when her 17-year-old daughter, Falmata, was brutally murdered by her uncle Awana, who accused her of disrespect.

This event occurred within a backdrop fueled by cultural norms placing high regard for hierarchy and respect, which Awana believed Falmata violated.

Despite attempts to resolve the issue through community mediation, Awana's anger led to the premeditated murder, reflecting deeply entrenched misogyny and the vulnerability of women in such societal structures.

The tragic incident highlights the broader issue of honor killings, often overlooked in rural areas like Bama, Nigeria, exacerbated by Boko Haram's insurgency.

Falmata's mother, Yakaka, who was briefly arrested, is now grappling with grief and the injustice of Awana's release after two months in detention.

The tragedy underscores the pressing need for systemic intervention to prevent femicide and protect women from cultural and familial-based violence, as emphasized by experts like Dr. Shekwolo.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter