A Skills, Literacy Initiative Is Giving Almajirai A Lifeline In Northern Nigeria

Millions of children sent to Quranic school by their parents and who ended up begging on the streets have become a major problem in Northern Nigeria. This foundation empowers more and more of them through a skill acquisition programme.

Khalifa Dankadai’s office is tucked into an alcove of a multicoloured school building he administers, directly across the busy intersection he had known since childhood. This is the main road connecting the Kano Emirate Palace and the State Government House, less than one kilometre from where he was born.

During the daytime, the ever-busy road is full of beggars, including those with disabilities. There are also scruffy-looking children as young as five, some of whose parents are on the other side of the street, stepping on car tyres to clean windshields before leaning to ask for alms.

Slapped by this reality since childhood, Dankadai felt compelled to do something about it.

When he graduated, people around him expected his father’s connections to land him a job at a prominent Abuja organisation, but he surprised them by pursuing his interests to reduce poverty, he told HumAngle in his plaque-filled office.

He stated the Khalifa Dankadai Charitable (KDC), which gets professional entrepreneurs to train young people, particularly those attending private schools, for a fee. KDC offers those skills at no cost to local public schools and Dankadai has been its executive director since it was founded in 2014.

After a year, he and his team realised that the people who would benefit most from their services weren’t formal students but rather children living on the streets, particularly the Almajirai who have been sent from faraway villages to fend for themselves despite being so young. It was at that moment the entire framework that KDC Foundation was based on changed.

The group’s work is based on the premise that poverty is not just a result of people’s income and expenditure, but because social and economic changes in their societies have failed to reach them.

The social exclusion of Almajirai often makes them feel inferior, hindering them from full social and economic participation. Dankadai believes that the only way to support them is to teach them new skills that could empower them economically. “When you mix with them, you can see how inferior they feel about themselves, and it affects them socially and psychologically,” he said.

The problem with previous approaches

In 2015, KDC began preliminary research into possible solutions to the Almajiri problem. The team, which began with volunteers, embarked on a pilot study in two local government areas in Kano. They intended to take a unique approach to resolve this issue in Northern Nigeria, which has resisted several attempts at modernisation.

They began by reading existing literature on Almajiri issues, particularly those published since 1999. KDC realised that “the major gap with those solutions was in the way they treated Almajiri schools as if they were formal systems that could be handled using a top-down approach”. That was why some interventions, such as the Almajiri schools programme implemented during President Goodluck Jonathan’s tenure, failed.

“They came with a syllabus designed for a formal system, but Almajiri schools should not be treated as such.”

Although they are still in operation, many of the Almajiri Model Schools have been converted to formal Islamiyya schools and are only attended by children whose homes are close to the schools. Other Almajirai from nearby villages continue to stream into the city to attend the same schools the new ones were supposed to replace, defeating the purpose.

According to Dankadai, the lack of accurate data on Almajirai has led to some solutions being based on speculation. “There is no exact number of Almajirai in Northern Nigeria because no one body tracks their inflow and outflow,” he said. According to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the figure is 10 million. The UN agency also says that more than 81 per cent of out-of-school children in Nigeria are Almajirai.

Dankadai thinks the figures are inflated because people mistake street children for Almajirai. “Most of the Almajirai children you see roaming the streets are mere beggars, some of them living with their parents or working as blind guides,” he said. He explained that by asking simple questions, people could tell the difference between young beggars and Almajirai. “Almajiri is the only person who understands certain technical terms. If you ask another boy you see during the hours he is supposed to be in school what Jagala or Satu means and he cannot answer, you can tell he is not an Almajiri.”

Another major issue is hygiene. Almajirai are usually dirty and scruffy, with begging bowls as their trademark. This has given the impression that anyone with an unkempt appearance is an Almajiri, even if he does not attend a traditional Islamic school. They rarely bathe or wash their clothes, and some are as young as five. The entrance rooms of the houses where they sleep are infamously stinky.

KDC desired to alter that perception. But to achieve this, it needed to interact with the Almajirai and meet their teachers. “People have assumed that because of their conservative tendencies, the teachers will be reluctant to cooperate,” Dankadai said, adding that they were instead “some of the most laid-back people” he has met.

He explained that all the teachers need is the respect they deserve, which they rarely receive from those who approach them due to their economic or social status. Understanding this provided KDC with a good approach that they leveraged on to carry out future activities.

The foundation inquired about the needs and desires of the Almajirai and the teachers. They avoided a common mistake made by most supporters of Almajiri reform: providing a designed curriculum for Almajiri schools. They asked the schools to tell them what they desired and how it could be designed, allowing them to meet their actual needs.

“Surprisingly, these people are not as resistant to change as they appear. They only despise the change approach that diminishes their status as school founders or teachers,” he added.

Step one: Research

In understanding the Almajirai, KDC followed a research stock and flow model. This was done in all the local government areas of Kano. They located existing Almajiri schools in communities where students are enrolled on a timely basis.

“We analysed how the flow of Almajirai is affecting the schools,” he said. From this, KDC found out that those in villages don’t beg. Also, the schools only need some sort of sensitisation to integrate skills acquisition and basic literacy. The major problems are with those who send their children to distant towns, and this was categorised into inter-state, intra-state, and cross-country inflow.

“The parents of these children have two answers to why they send their children to distant places for learning,” he said. The first is related to the question of poverty. The parents believe if you don’t send your child to beg during his early years, he will beg when he grows up.

“The other one is they think a child close to his parents can’t be serious in his studies,” Dankadai added. Between these excuses, there are some issues, but most of them fall under poverty and worldview.

Going into the schools, KDC found that most of the children are sent and then neglected. And that’s where the problem of begging and hygiene comes in.

“A parent can send his small child to a distant Almajiri school and abandon him for over five years without any form of communication,” he explained. The dormitories are also dilapidated in most schools and left to society’s mercy. The teachers don’t drive salaries or stipends from the students except for a few schools where weekly fees (Kudin Laraba) are collected.

Redesigning the schools

“To solve these problems, we came up with an idea of redesigning the schools to not only look at the teaching, but the teaching methods,” Dankadai said. KDC concluded that the teaching methods at Almajiri schools should come with guidelines and a new curriculum.

“Under the guidelines, we proposed that all Almajiri schools should have structures that include a good recitation hall, a hygienic toilet and skills corner where students will be trained on different skill acquisitions,” he said. All teachers were to follow a new curriculum designed for them.

The school should also have an administrative section where the inflow and outflow of the students are recorded, and parents and communities should support the integration of mainstream education into the schools, “not necessarily with money”.

Under the curriculum, KDC proposed that apart from mainstream education, other Islamic teachings, including jurisprudence and theology, should be put in the system, and vocational and life skills should be at the foundation of the schools.

“You may come across a student who has memorised many Quranic verses but cannot pray or read other Islamic books. Furthermore, as society evolves, these children should be taught new skills relevant to the modern era. These are impossible to achieve without literacy and vocational skills,” Dankadai said.

Community Library Project

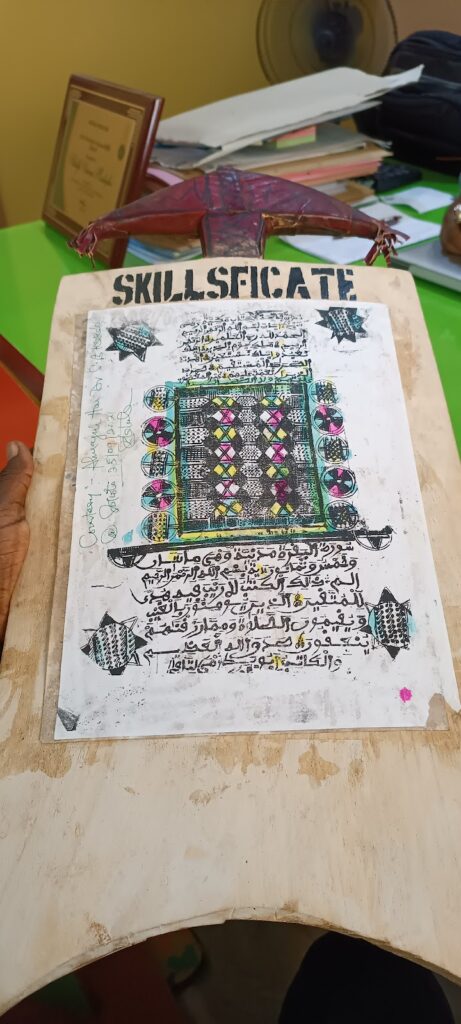

In 2016, KDC came up with a pilot project to improve the quality of education received by the children. The Community Library Project (CLP) started in two local government areas in Kano, Nassarawa and Gwale, and due to limitations in funding, it used the local government headquarters as skill acquisition and literacy centres. Two hundred Almajirai were selected for the maiden edition of the programme, 100 from each local government area. They were trained for a year and sponsored to attend formal schools.

The project’s success later led to expanding it to phases 2 and 3. CLP started with small participants who were taught basic literacy and arithmetics for a year. “When they graduated for only a year, some of them were able to start primary schools and others went as far as securing admission at junior secondary schools,” Dankadai said.

Idris Abubakar is one of the beneficiaries from Gwale. He began making shoes after gaining admission into a secondary school. Mallam Mustapha, his teacher, confirmed improvements in his behaviour and studies. “Through some forms of behavioural change by association, he has influenced even some students around him with hygiene,” Mustapha told HumAngle.

Mallam Ayuba Ahmad is another Almajirai teacher whose students, including his son who recently graduated from primary school, benefited from the literacy and skill acquisition programme. His school is located in Kawo, a town on Kano’s outskirts. He told HumAngle the programme has increased his students’ overall self-esteem.

“When they first arrived from their villages, they began by begging. Despite the fact that it is unavoidable, we dislike it. So when the skill acquisition programme reached us, we jumped on it right away, and they are still reaping the benefits,” he stated.

Mallam Ahmad went on to say that when the government renewed its efforts to stop Almajirai from begging, most of his students were unaffected because they had a job that they could get income from to buy food. “Some of them used to be into manicure, but the skill programme promoted them to shoemaking and tailoring,” he explained.

Two of his students who spoke with HumAngle are from Kankara village in Katsina, also a state in Northwest Nigeria. Both said that they have stopped begging since receiving the training. Buhari Isa, 15, learned tailoring but switched to shoemaking due to the lack of a sewing machine. “My new job is better than begging,” he said proudly. Mas’udu Tukur said the same thing but added that he needs support to grow his business.

Scaling and recognition

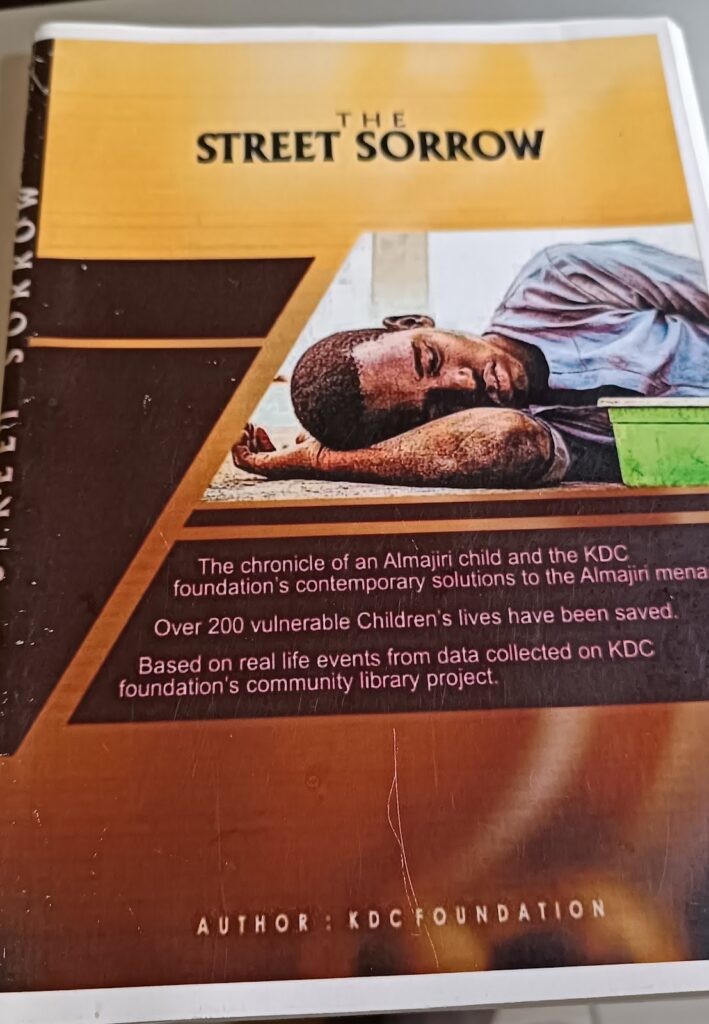

At the end of the programme, a book about the experiences of some of the selected Almajirai was published. According to the post-project evaluation report, the overall behaviour of the students who participated in the programme has improved. The skills they learned, ranging from tailoring services and shoemaking, have supported their lives. Best of all, they have stopped begging.

The pilot project’s success secured the foundation partnership with the United States Embassy in Nigeria. The project, CLP 2 and 3, was later expanded to six Northern Nigeria states, selecting 10 schools with an average of 100 students from each of the six states from the North, making a total of 6,000 participants. The states are Kano, Jigawa, Katsina, Zamfara, and Sokoto in the Northwest, and Niger in the North-central region.

Seeing this effort, the Federal Government of Nigeria signed a memorandum with KDC through the N-Power project for all the graduates passing through the programme to work with the foundation. “Whenever we need some facilitators, we only write to the government and they send us N-Power beneficiaries through the Tsangaya Board,” Dankadai said.

Film making and challenges

The experience of the CLP project has been turned into a film to raise awareness about the condition of Almajirai and their schools in Northern Nigeria based on findings. The film was made in Hausa language with English subtitles and is aired by Arewa 24, a popular satellite station in Northern Nigeria. “We are working on how to make it a series on the CLP 3,” Dankadai said.

While this is not the first film made about the Almajirai, this is the first that has gained widespread attention through a popular television station. Titled Tsangayar Asali, the film’s aim is to show the real reasons people sent their children for Almajiranci before the institution deteriorated.

Despite these achievements, KDC has stated that it has faced numerous challenges. “The first issue was funding,” Dankadai explained. “We had to devise a fundraising activity through some fashion shows, and despite Kano State’s conservative nature, we were able to get a lot of people participating for a fee,” he recalled.

Also, the project cannot reach all Almajirai in Northern Nigeria. However, KDC believes that the main hurdle is getting started, and that the organisation’s activities will influence other schools to adopt the system as time passes.

There is also one complication — the lack of a standard inter-state government agency managing Almajiri schools. “Not all states have Tsangaya management bodies, which makes approaching some of them difficult,” he explained. In the absence of such a regulatory body, some Almajirai’s parents, who are resistant to change, would relocate their children to another state.

KDC is certain its model could be implemented anywhere in Nigeria with almajiri schools.

“Our next goal is to ensure the sustainability of these schools,” Dankadai said, adding that this would encourage others to implement similar solutions. “We designed these schools to be models, and our long-term goal is to see them everywhere, particularly in Northern Nigeria.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter