2023: Examining Nigeria Electoral Body’s Plan To Conduct Election In IDP Camps

Almost three quarters of local government areas in Borno State will be voting in IDP camps due to insecurity according to election regulators. Many affected voters are critical of the arrangements and still have fears over the safety of going to the polls.

Voters from almost three-quarters of Borno’s Local Government Areas will cast their ballots in the forthcoming elections in some form of displaced people’s camp or polling station that is not their registered home.

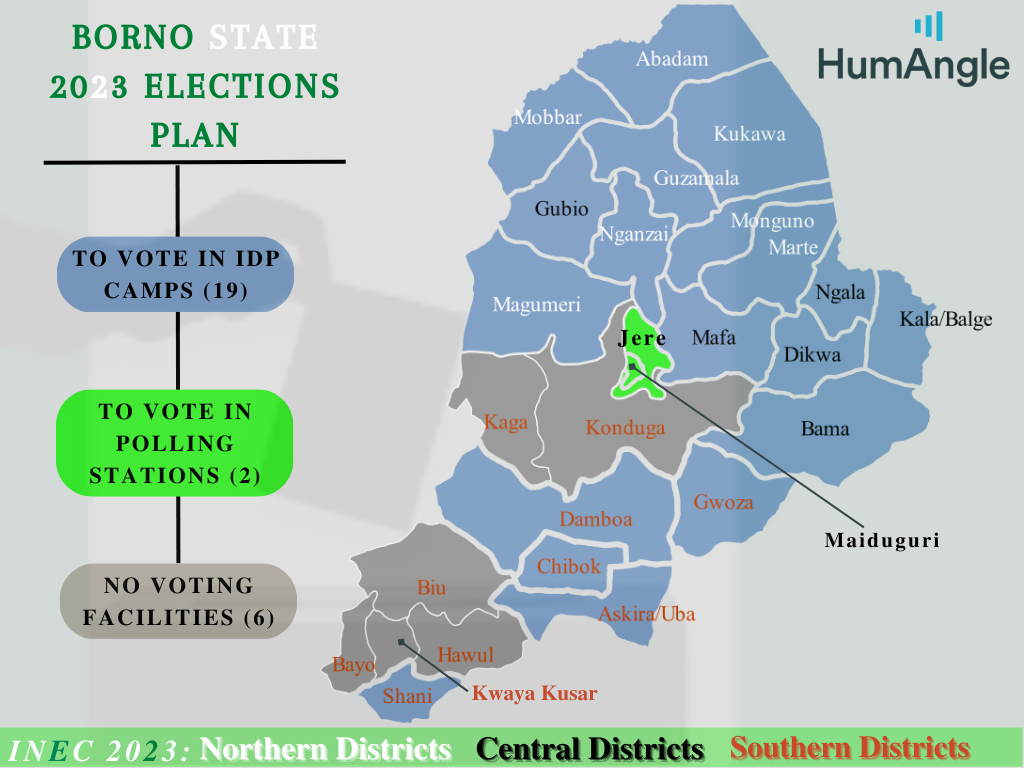

Voters in at least 19 of Borno’s 27 Local Government Areas (LGAs) will vote in “resettlement” camps, set up to hold internally displaced people before they can be returned to their homes, according to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), Nigeria’s sole regulatory body for elections.

This means it is still too insecure across some 70 per cent of the LGAs in Borno for them to hold elections in the voters’ original homes.

The 2023 election will be the third time IDPs in Borno State, Northeast Nigeria, will have to vote for their chosen leaders at polling stations far away from their constituencies.

Votes cast

Most Borno residents, especially those from the hinterlands, voted in IDP camps during the 2015 elections. In 2019 elections were again held in IDP camps, even though voters in some of the relatively safe local government areas had to be transported by the state government to their council areas, where they exercised their civic duty.

With the improved security in the state, especially in the hinterlands, the state government had last year managed to conclude the return of IDPs in Maiduguri, the state capital, to their ancestral homes.

As in previous elections, in the camps, each local government area will have a designated place, voters will queue according to their wards, and then the queue will be divided into their polling units where votes will be cast.

By the last quarter of 2022, the Borno State government shut down all the official camps in the state capital, Maiduguri, and relocated most of the inmates to the headquarters of their local government areas.

Those who felt it was unsafe to go back home were allowed to live within the host communities where they had to take responsibility for their own welfare.

Other IDPs who, from the onset of their displacement, had chosen to live in dozens of “unofficial camps” that still litter the nooks, crannies, and outskirts of Maiduguri, were not considered for the official return because they were not the responsibility of the government.

Those in “unofficial” camps will effectively lose their vote if they do not travel to the areas where the election is taking place for their LGA.

INEC has not yet calculated how many voters could be affected by this.

Change of pattern

INEC in Borno state had announced that elections for nine of the ten council areas in northern Borno would be conducted in the temporary IDP camps located at the local government headquarters. For the Central Borno district, only people from two of the six local government areas will vote within their home polling units.

The electoral body said the same situation would play out in the southern zone of Borno, where only four out of the nine LGAs would wholly vote in polling units within their communities – while others would converge in mega camps to cast their ballots.

Borno State governor Babagana Zulum recently said that there are locations of the state that are still flashpoints of attack by Boko Haram, which have remained inaccessible.

The governor’s claim has not only bolstered INEC’s justification for holding the next elections in IDP camps, but also questioned the electoral body’s ability to safely deploy election materials and personnel to those remote local government headquarters which are not currently vulnerable to attack.

The Borno REC said, “INEC has mastered the art of conducting elections within the IDP camps with the experiences of the 2015 and 2019 elections.”

“In 2019, apart from Abadam and Kukawa, all LGAs that had insecurity issues voted at the headquarters of their respective local governments.”

INEC believes the situation will be a bit easier during the 2023 elections because most IDP camps in Maiduguri are closed, and most of the inmates have been returned to their LGAs.

“For the coming 2023 elections, only Maiduguri Metropolitan Council and Jere local government area will vote in all of their respective polling stations while the rest will vote in camps,” the REC further clarified to HumAngle.

“The same applies to the northern and southern districts of Borno, where 11 local government areas will vote in camps.”

INEC arrangement

Borno State has 27 LGAs, of which the north senatorial district has 10 LGAs, the south has nine, and the central senatorial zone has eight.

By INEC’s arrangement, the local government areas in the northern senatorial zone – Abadam, Guzamala, Kukawa, Nganzai, Monguno, Magumeri, Marte, and Mobar – will all vote at centralised polling stations within the temporary IDP camps located in the local government headquarters.

In the Southern Borno senatorial district, Askira-Uba, Chibok, Gwoza, Shani, and Damboa will entirely or partially cast their votes in camps.

In Borno Central senatorial district, INEC said all the electorates in Mafa, Bama, Dikwa, Gamboru-Ngala, Kala-Balge and Gubio LGAs will vote in camps.

The REC clarified that all the registered voters in the local government headquarters where there are temporary IDP camps will be voting in polling centres stationed there, “regardless of whether they are IDPs or members of the host communities.”

Some of the LGAs, like Bama in the central part of Borno and Gwoza in the South, which have populations residing in both the main towns and the IDP camps, are allowed by INEC to have a setting that may be a little bit different.

For example, HumAngle learned from sources in Bama that the resident stakeholders had raised concerns that it was needless for INEC to ask them to vote in the IDP camp since they are well settled in their homes within original communities.

“We in Bama cannot be forced to go and vote in camps – not after we have lived peacefully for over three years now in the town,” said one Mommodu Gulumba, a local opposition politician.

Gulumba said voting in IDP camps had, in most cases, favoured only the All Progressive’s Congress ruling party.

“The ruling party in the state usually has the power and the resources to manipulate voters, especially the vulnerable IDPs,” he alleged. “That was why we made it clear to them that the original polling units in the township should be retained so that people can vote there, while the IDPs from the hinterlands of Bama local government can have theirs stationed within the camp.”

HumAngle contacted the INEC in Borno State to verify this claim. The Commission’s spokesman, Abba-Kyari Liberty, said: “the arrangement for Bama will allow people in the host town to vote in their polling units while others who had to migrate from other communities within the LGA will have to vote in polling stations within the camps.”

How IDPs feel

As in 2019, the electoral body insists that no special polling centres would be created in unofficial camps in Maiduguri. INEC has insisted that IDPs from any remote local government that reside in Maiduguri can only vote within their original local governments where they are registered.

An IDP from Mafa, Babangida Isa, who lives in Muna Camp, said the Borno State government had arranged with the various local authorities to organise vehicles that will convey eligible IDPs in unofficial camps and host communities in Maiduguri to their council headquarters on the eve of the election days.

“During the last general elections, the majority of us who voted had to risk it all to travel in long convoys of buses to our local government headquarters where we cast our ballot,” Isa said.

“They said we have not registered IDPs, and for that reason, our people here have suffered neglect and hunger for all these years. But when voting for them, they will bring long buses to take us to our local government to vote. The last experience was dehumanising because you are to sleep out in the open on the eve of the election without anyone caring if you have eaten. After the voting, you must rush back to the buses to take you back to the city, or you are left behind.”

Amina Usman, an IDP from Mafa, who still lives with her aged mother at Muna Camp in Maiduguri, said she might not go to her community to vote in the coming election.

“The last time we had to go and vote at the local government headquarters in Mafa, many suffered,” she said.

“Yes, the politicians promised us certain allowances and only gave us less than what was due to us. Some did not even get the money. So I don’t feel compelled by any reason to follow them to go and vote only to be returned here and dumped because they say we are not officially IDPs.”

The Speaker of the Borno State House of Assembly, Abdulkarim Lawan, had recently voiced his concern about how his constituents would vote because his LGA, Nganzai, which is one of the major strongholds of Boko Haram remains a no-go area. The entire geographical space of the Nganzai local government has been under Boko Haram occupation for over eight years.

Nganzai has been casting their votes in IDP camps since 2015. How the constituents will participate in the next general election is now a big concern for politicians like Speaker Lawan because his people are more dispersed with the closure of the official camps.

“I feel sad that the situation has not been improved security-wise in these locations,” he said.

“In 2015, we conducted elections partly in IDP camps, and in 2019 all electoral wards of Guzamala had their polling units in IDP camps, and sadly the same thing may likely be the case for us going into the 2023 election because we don’t even know where we are going to cast our votes. I am confused because, more than ever before, our electorate is scattered everywhere now. Some are camping in Monguno local government, some in Nganzai, some in Maiduguri, and many in Niger Republic. I’ll say we don’t know exactly where we are to conduct our elections because there is no specific location where we can say this is where the people of Guzamala are being camped.”

Bulama Modu, 29, said he was from Limanti Ward in the Mafa local government area of Borno State before fleeing Maiduguri to evade Boko Haram attackers. Now living in Muna IDP Camp, the secondary school leaver said he had been voting since his early 20s with the hope that politicians in his community would help him to further his education.

“I started voting those years when there was peace in our community. For the 2019 elections, we travelled to Mafa to cast our vote at all the elections that were conducted at the time,” he said.

“We are participating in politics, but our leaders here are cheating us,” he alleged. “We see interventions come to this camp, but it doesn’t reach us, even though we all took the risk of travelling to Mafa to exercise equal voter rights.”

Bukar Kawu, 44, a community leader at Muna camp, said the majority of the residents collected their PVC, but he is not sure of where his people would be taken to vote. He is originally from Marte.

“We don’t know whether the election will still be conducted at our local government or it will be here in the camp,” he said. “In 2019, we were carried to the local government (Marte) to cast our vote. It will be easy if it can be done here without the stress of travelling.”

Maimuna Malam, a mother of six children at the Muna camp, confirmed she has her voter card. She said though she would still exercise her civic role by travelling to Mafa to vote as long as the government provided the vehicle for transportation, her primary concern was the lack of food to feed her children.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter