12 Years After Government Initiative, Almajirai Roam Nigeria’s Streets

In 2009, the then Nigerian president, Goodluck Ebele Jonathan established Model Schools for Almajiris to reduce the number of out-of-school children in the country and also to promote their relevance in the society.

Mallam Abbas speaks with resentment in his voice. He expresses dissatisfaction with the way almajiranci — an informal educational system that derives its curriculum from the Qur’an — is portrayed these days.

Abbas is a resident of Baban Saura Community in Kaduna state, Northwest Nigeria, and has been a Qur’anic teacher for young people, known as almajirai, for 24 years. Almajiri (plural: Almajirai) is a Hausa term for referring to the students in the informal education system where the students acquire Islamic knowledge from scholars. The students are sent to faraway cities for this acquisition.

“The practice is done across the Muslim majority in West African communities. The state and emirs adequately funded it, alongside parents of the children, and other organised platforms, and this covered shelter, clothing, and feeding for the students. The system has since deteriorated after the British invasion,” writes Hauwa Shaffi, for Minority Africa.

Since setting up his tsangaya (Quranic school), Abbas has received countless organisations and groups who had ideas on how to eradicate street begging by almajirai, but it never worked.

“These people don’t even ask us what we need. Some come with cartons of food or wads of cash, but this all eventually finishes. What we need is inclusion, we are also part of the society,” he laments.

About 81 per cent of out-of-school children in Nigeria are presumed to be almajiris. Before the establishment of western education, almajiranci was a form of schooling widely practised in the northern part of the country.

Then, tsangayas were usually supported by the host community as it was a system that gave back to society, but after western education became customary this support shrunk until the system totally collapsed. But this did not mean the practice had been eradicated.

Up to now, many families uphold the thought of formal education being sacrilegious and continue to send their wards to Mallams in far-off places to learn the Qur’an.

Because most of these children are sent with little or no food or pocket money, these Mallams are left to cater for them by imposing Kudin Sati (weekly fee) on each student. With the caution that begging is better than stealing, these boys move from neighbourhood to neighbourhood carrying plastic bowls for alms or food collection.

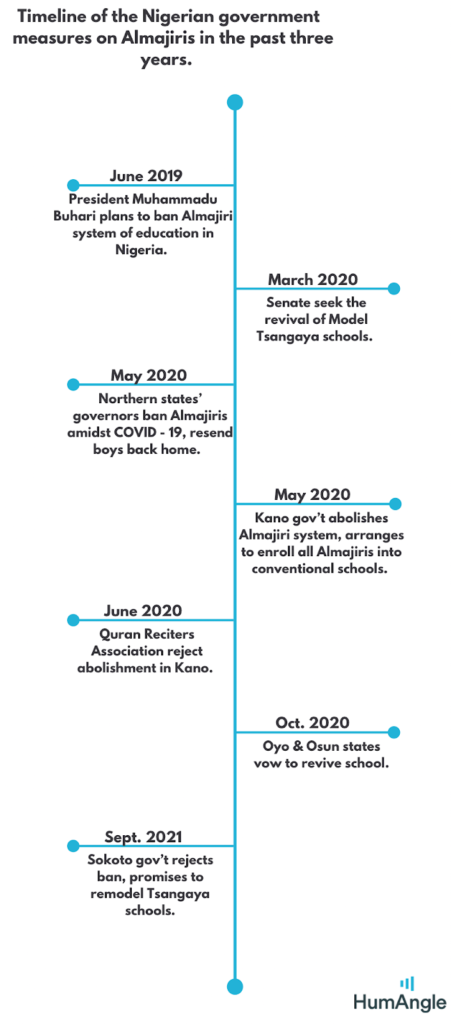

Criticisms and government effort

This method of acquiring Islamic knowledge has come under serious condemnation as many of these children have been exposed to a life full of vices. Some face different forms of abuse even from their teachers while others are lost to disease, hunger, or both.

Mallam Abbas told HumAngle he has had complaints about how much of a menace boys like his students are. “Every day I hear about how bad what we do is or how my students can become criminals, but no one is suggesting a strong solution.”

Abbas shares instances of how a lot of people have benefited from the system before it lost its glory. When he graduated from being an almajiri in the 1980s, he taught in a government secondary school before he established his own Quranic school.

“Nowadays the Mallams are not committed and some of the students do not finish their learning, which can make them seem like they are not useful in the society,” he explained.

In 2009, Nigeria’s former president, Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, began building and rehabilitating Model Tsangaya/Almajiri Schools across Nigeria.

The schools were intended to infuse formal learning into Islamic education. He also revealed that the schools were built to make almajirai employable and to check incessant crisis and insecurity.

Though the project was seen through completion, many of these schools have either been abandoned or the vision for setting them up was lost. Begging on the streets by almajirai still persists as several other measures by subsequent governments, both federal and state, continue to fall short.

Model tsangaya/almajiri schools.

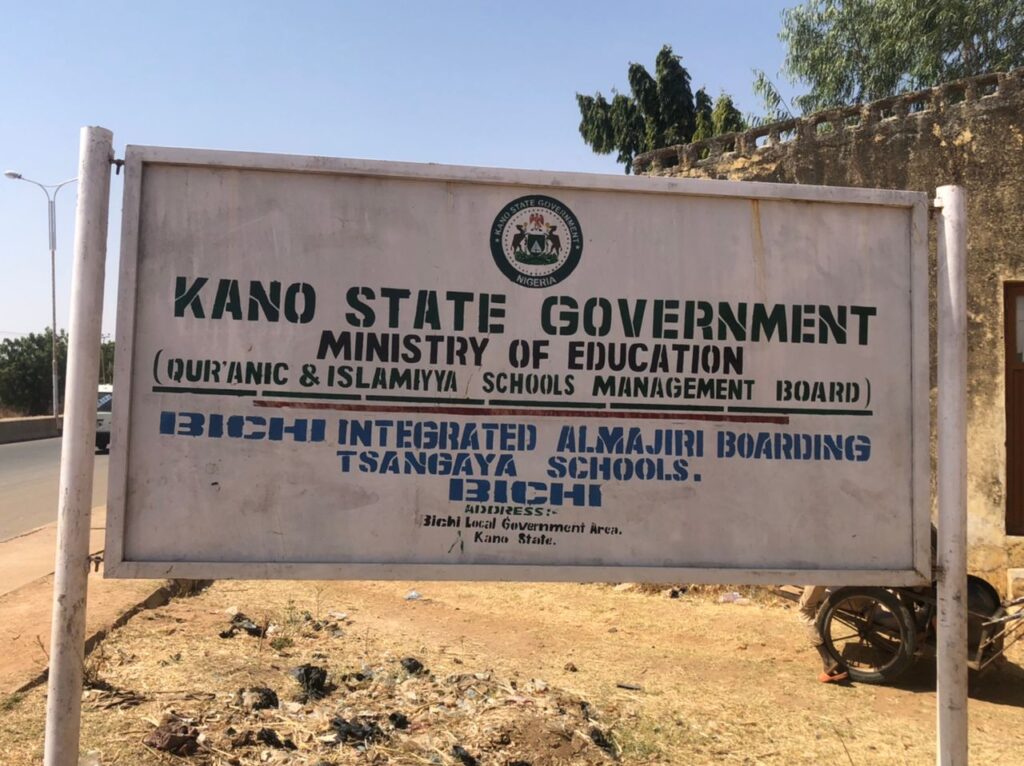

Today, a few of the Model schools are being utilised for their purpose. Bichi Integrated Almajiri Boarding Tsangaya Schools in Kano State, Northwest Nigeria is one of them.

Sani Auwalu, a resident of Bichi Local Government Area (LGA) has three of his children learning in the school. “We are very proud of this establishment, in the entire Bichi no school gives this much knowledge to children and teenage boys like this one,” he said.

Auwalu added that at first, he wanted to take his son to a Makarantar Allo (a local Islamic school) in Danbatta, a local government in Kano that is 72km away from Bichi but when the school was built he decided to give it a try.

“I saw how he had improved academically and his siblings too wanted to join him in the school. Now they are all in school.”

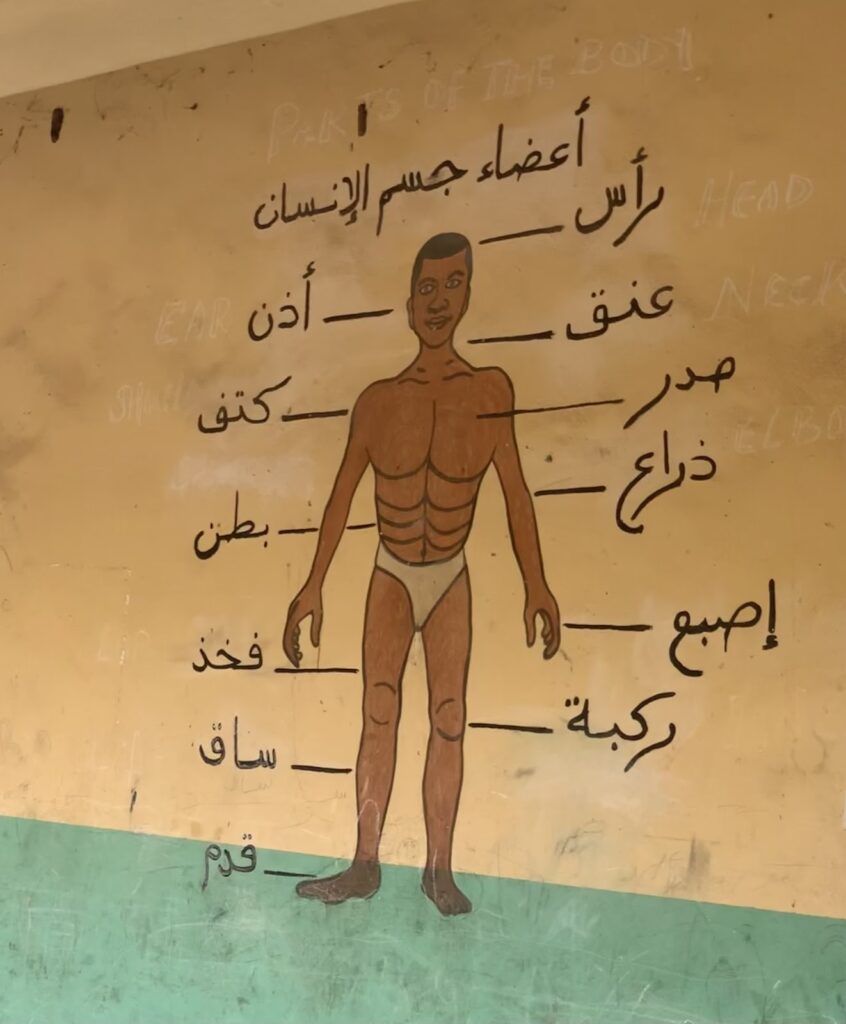

The school teaches Mathematics, English, History, Biology, and Arts as the Nigerian curriculum recommends. Then there is Arabic, Quranic, and Islamic Jurisprudence studies among several others. The school also provides breakfast, lunch, and dinner so students do not need to move around in search of food.

Management at the Bichi Almajiri Integrated Tsangaya School located in Kano State denied HumAngle audience without the state government’s consent. How the school seemingly operates better compared to others is unknown.

At Model Islamiyya Primary School, Kuntunku, located at Gwagwalada in the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja the school was still in session at the time HumAngle visited.

Built and equipped in 2010, it only started functioning in 2017, enrolling students from primary one to six.

The school also teaches subjects recommended by the curriculum in the morning and Islamic subjects from noon. However, the Head Teacher Admin, Jibrin Alhassan, told HumAngle that the Islamiyya aspect of the school is slowly fading away due to the lack of teachers.

The school has other challenges such as lack of water, textbooks, and even though there’s a computer room fitted with desktops, the lack of electricity in that area makes them redundant for learning.

Safyanu, a resident of Kutunku community suggests that the school was meant to be a Model Tsangaya to curb street begging by almajiri children, but after it was abandoned for up to seven years it was changed into a Model Islamiyya Primary School.

However, many residents of the area also refer to it as a school for almajiri even though the headteacher insists it is not.

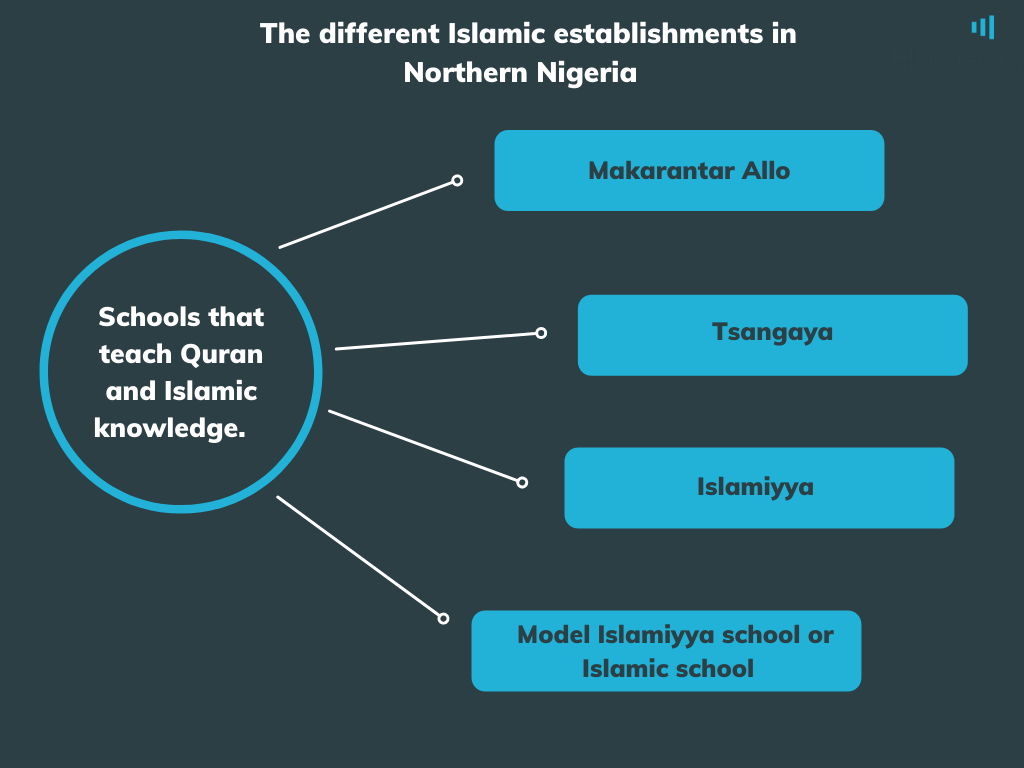

The difference between the various Islamic schools

Makarantar Allo, Tsangaya, Islamiyya, and Islamic schools all hold lessons that teach Arabic, Qur’an recitation, Islamic jurisprudence, and other subjects that strengthen the Muslim faithful in Islamic knowledge. However, the methods of delivery significantly differ depending on which.

Makarantar Allo is a local Islamic school that usually has one or two teachers. The setting is usually in an open space with wide mats spread on the ground which allows students to sit with their legs tucked beneath them. They learn with wooden slates that are referred to as allo in Hausa. The part of the Qur’an they are learning is usually written on those slates and washed off for continuity when it is fully memorised.

Tsangaya is the same as Makarantar Allo but is more of a boarding school version. This type of establishment attracts students from far places who are required to stay under the care of their teacher until they have learned all that is expected of them. The students here are Almajiris.

Islamiyya, on the other hand, is a facility usually attached to a mosque where there are teachers who specialise in the different Islamic subjects they teach. It is more structured and there are classes with desks and chalkboards ranging from class one to four (or six). Students are required to pay school fees, wear uniforms and buy the necessary textbooks for their learning.

Model Islamiyya/Islamic schools are those that infuse conventional education with Islamic studies. The teachers are specialised and it has a structure, just like Islamiyya. These types of schools usually arrange subjects recommended by the National curriculum from morning to noon, and Islamic classes from noon till evening on the school’s timetable.

Why almajiri system prevails

The former president’s project aimed to clampdown on the number of almajiris on the streets had potential, however, the planning process did not take into consideration the people it was supposed to benefit, Udosen Namse, an Education Development Expert, said.

Namse posits that there was no proper school mapping. “The relevant stakeholders were not carried along and so a lot of those it was meant for do not know it exists,” he pointed out.

This is in line with Mallam Abbas’ claim of only hearing about it but not knowing if the establishments were completed.

Namse also said that most times demographic analysis isn’t done. “Some of these communities have more children between the ages of five to ten, and then a secondary school is built. How will they be enrolled into them?”

He added that extensive orientation was necessary even before the schools were built because it was beyond just providing facilities.

“We are talking of a belief that has been passed from generation to generation. You cannot just force a system on people if they don’t see how it can add value to them.”

In other accounts, Ahmad Bunza, in an investigation by the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR), claims that the project is failing because the concern was more on gains obtained from the contact rather than the quality of education.

Bunza is a student in one of the schools. He alleges that billions were spent on building and setting up the educational institution but not as much is being spent for the welfare of teachers and students.

Additional reporting by Aliyu Dahiru

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter